So, y'all know how much I love my home town of Chattanooga. And there is a centerpiece of the city – the Walnut Street Bridge. It spans the Tennessee River and is now one of the longest pedestrian bridges in the world. It connects the restaurants and galleries of the Arts District to the restaurants and shops of the Northshore. On any given day scores of people can be found making their way across planning on a fun outing, putting the cares of the world away for an hour or two.

But it wasn't always this way. Because in 1909, a black man, Ed Johnson, was lynched from that very bridge.

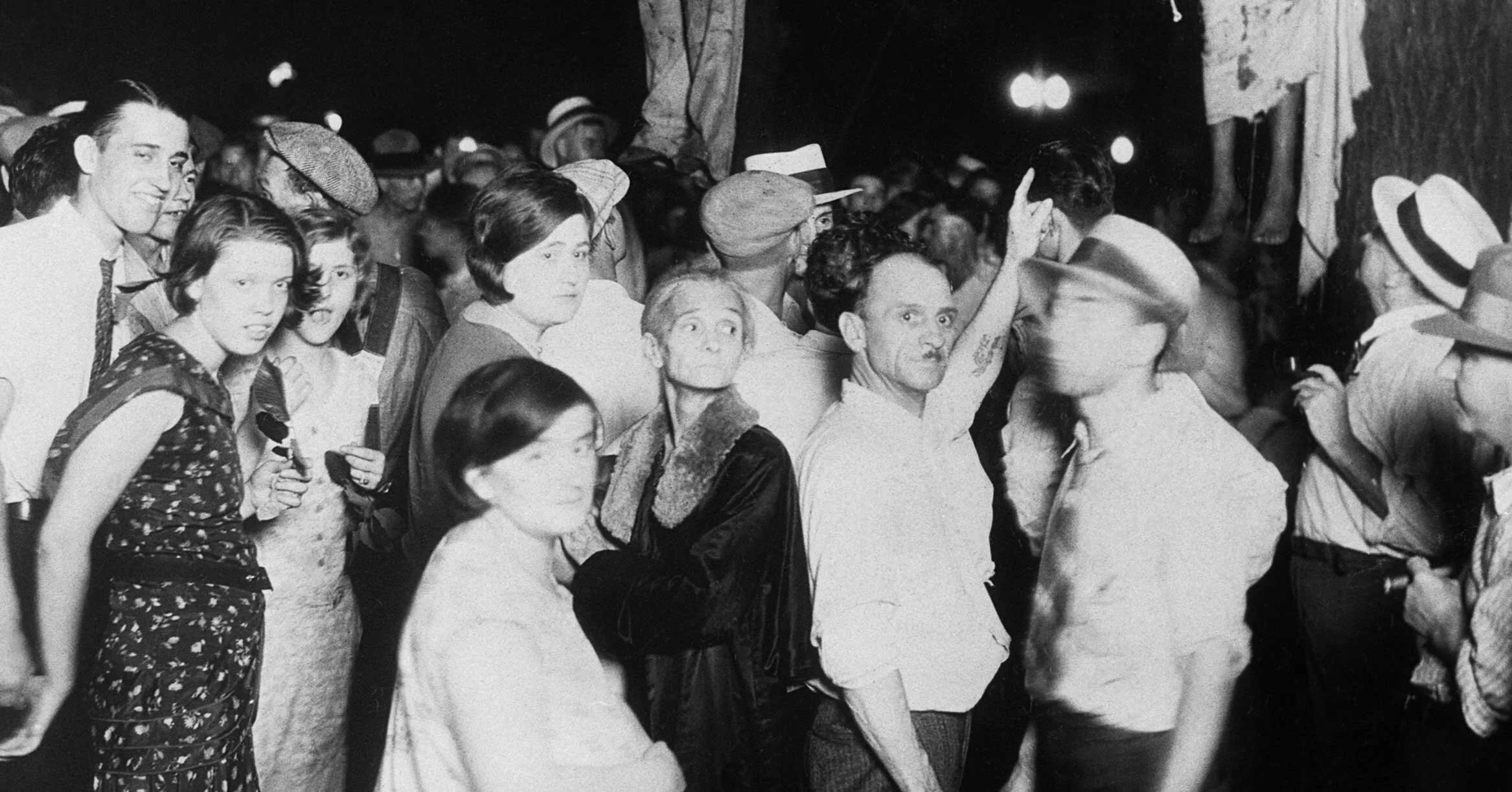

Accused of assaulting and raping a blonde and beautiful twenty-one-year-old white woman, Johnson was convicted on trumped-up evidence in a quickly arranged trial that left many, even some of the most ardent segregationists, wondering about the verdict. On appeal, the United States Supreme Court stepped in to stay the scheduled execution in order to allow the case to be investigated. But an angry mob of some seventy-five men stormed the county jail where Johnson was held. They seized him and then dragged him to Walnut Street Bridge, and hoisted Johnson onto the second span of the bridge. His final words were, “God bless you all. I am an innocent man.” Then the lynching rope gave way before the strangulation was complete, and Johnson fell onto the pavement below. One of the sheriff’s assistants fired multiple shots into his body. The murderous mob dispersed as quickly as it had assembled. Around midnight, a horse-drawn cart from a “colored” funeral home came, and three men gathered up the body of Ed Johnson. According to the coroner, his body had been shot more than fifty times.

This abomination led to the only criminal trial ever conducted by the United States Supreme Court. President Theodore Roosevelt condemned the lynching and sent two Secret Service agents to Chattanooga to investigate the case. As a result, Chattanooga Sheriff Joseph F. Shipp, a former officer in the Confederate Army, was charged only with criminal contempt. Shipp denied any involvement, but evidence indicated that he had led the lynch party. He was tried by the Supreme Court, found guilty, and was sentenced to ninety days in a federal prison in Washington, D. C.

Ninety days.

After serving two-thirds of his sentence, Shipp was released early for good behavior. He returned to Chattanooga, where a crowd of some 10,000 local whites turned out to give him a hero’s welcome, waving American and Confederate flags while a band played “Dixie.”

It's hard to find any grace in what happened that night in Chattanooga or afterward. And sometimes it seems that that dark evil of the heart will continue to flame up, catching others up in it.

I imagine that's what happened in our Gospel reading with John the Baptist. A ruler who wanted to meet both John and Jesus, ends up standing by as evil feeds on evil, darkness begets darkness, and soon a group gathered for a meal becomes a mob licking their chops over a brutal execution and beheading.

And I wonder about those bystanders. After the Baptist's head was presented, how long did it take for anyone to look away in disgust and horror? And did anyone dare to speak up and say, “Herod, you will regret this”? But maybe there something more to the story, and maybe in that something more, there is the grace.

Maybe this story erves a different purpose altogether. Maybe we hear this story today so that we can stand in it for a while so that we, each of us, might become even more deeply aware of the senseless tragedies which play out all around us, even those of our own making, when we prioritize our pride or our own ambition or love of power and desire for achieving our goals on the heads and lives of others.

Maybe this story is here to force us to look at the dark brutality we as a nation of so many Christians are capable of causing before we can begin to see the small light of grace. I wish this were not true, but I wonder if the story is included here to force us to take a hard look at what can come to be when we as a people use power and wealth and influence in a way that make others expendable.

Because standing here in this story – this can be the beginning of change. This can be the beginning of renewal. This can be the start of grace given and grace received. Because we are also Herod. And we are also John. And we are everyone in between. And maybe the beginning of grace is this: that I recognize that my action – and inaction, my speaking – and not speaking, so often makes me complicit in what happens in this nation, this world?

Could that, in fact, be the beginning of grace given and grace received, as we are forced to step back and look, to reconsider and begin again? As we recognize the need for healing and for new beginnings whose only source can only be the God who loves us and yearns to embrace us all? God who sees us as so very loved and calls us to God's kingdom, and in Jesus Christ shows us how to do the same with others?

Is this why Mark tells us this horrible story in all of its gory detail? I don't know for sure, but I think it may be so. Maybe there is grace to be seen here, even here.

In Chattanooga, on the Sunday before the lynching, several hundred Christians from St. James Baptist Church, a leading black congregation in the city, had gathered at the jail to worship and to minister to Ed Johnson. At this time, Johnson professed his faith in Christ and was baptized “according to the Baptist style”— in the jailer’s bathtub. Johnson was received into the church by voice acclamation with rejoicing over the salvation of a new child of God and a picnic lunch, right there in the jail.

Many of those who witnessed the jailhouse baptism would be among the two thousand who later made their way to Pleasant Grove Cemetery later in the week for Johnson’s funeral and burial.

And ninety-four years after Johnson was brutally murdered on Walnut Street Bridge, another trial took place in Chattanooga. This time his conviction and death sentence were overturned – posthumously – in a Tennessee court of law. Judge Doug Meyer remarked, “It really is hard for us in the white community to imagine how badly blacks were treated at that time. It’s still a continuing struggle.” Sheriff Shipp’s grandson, who was alive at the time, expressed a contrary view. “It’s water under the bridge, as far as I’m concerned,” he said. “We can’t go back and undo things that were done ninety years ago.”

I don't believe that. I'd prefer to stand with those African-Americans who, on hearing this new verdict began to sing together, filled with love and grace:

It’s a mighty long journey,

But I’m on my way—

It is a mighty long journey

But I’m on my way . . .